FlashAttention 123

This is a learning notes about the FlashAttention. We all know that the transformer architecture has revolutionized deep learning, especially in natural language processing. However, the standard attention mechanism can be incredibly demanding in terms of memory and compute, particularly when dealing with long sequences. This is where Flash Attention v1-3 comes in, offering a clever solution to these challenges.

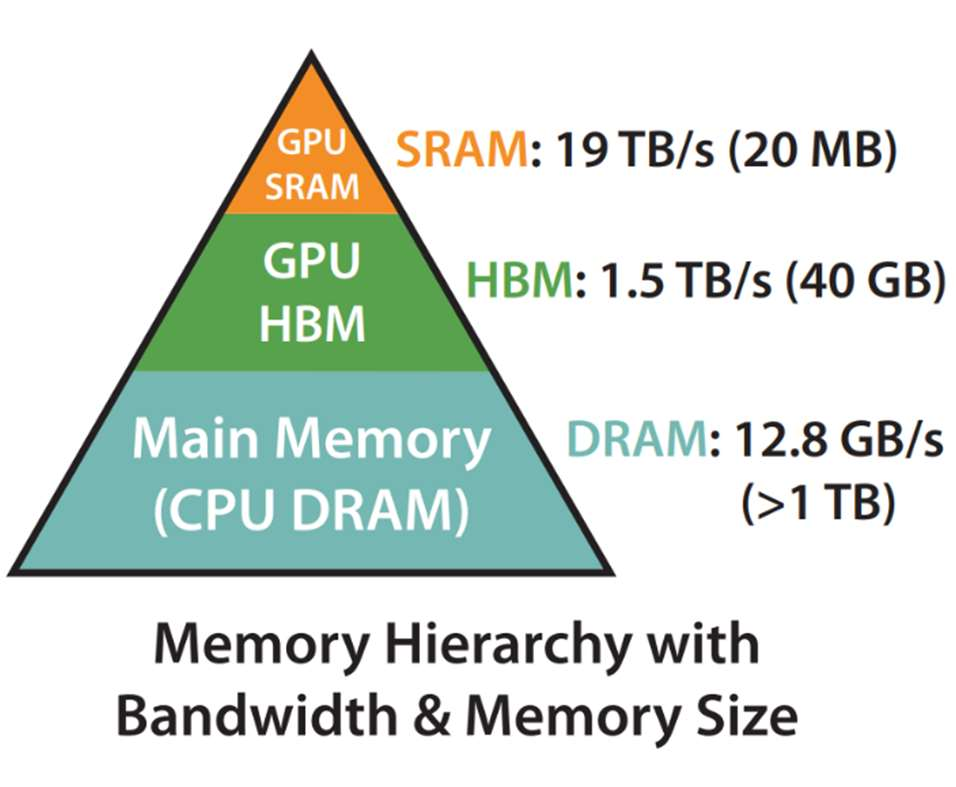

GPU Memory Hierarchy: SRAM vs. HBM

GPUs utilize a hierarchical memory structure, with each level having different speed and capacity trade-offs. Understanding this hierarchy is key to appreciating Flash Attention:

- On-chip Static Random-Access Memory (SRAM): This is the fastest memory available on the GPU, located directly on the processing chip. It offers very high bandwidth but is limited in capacity. For example, an A100 GPU has 192KB of SRAM per streaming multiprocessor.

- Off-chip High Bandwidth Memory (HBM): HBM is a larger but slower memory compared to SRAM. It provides more storage space but has lower bandwidth, making it slower to access. A100 GPUs have 40-80GB of HBM.

The speed difference between SRAM and HBM is significant. SRAM has a bandwidth of around 19 TB/s, while HBM bandwidth is around 1.5-2.0 TB/s on an A100 GPU. Efficient computation on a GPU involves maximizing the use of SRAM, thereby minimizing the need to access the slower HBM.

In GPU computations, data flows through three main steps: data is first loaded from High-Bandwidth Memory (HBM) to SRAM (cache), computations are performed on registers using data fetched from SRAM, and results are written back from SRAM to HBM. The transfer between HBM and SRAM often becomes a performance bottleneck due to the significant speed disparity between these memory levels. Techniques like Flash Attention aim to mitigate this by reducing the frequency of HBM accesses, optimizing memory usage and computational efficiency.

Vanilla Transformer Attention Mechanism on GPU

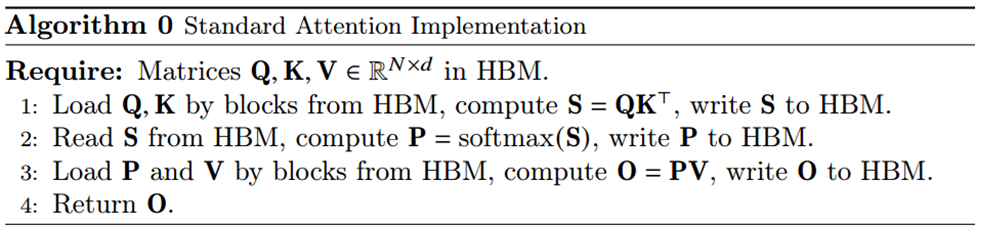

The standard attention mechanism in a vanilla transformer processes data as follows:

- Load \(Q\) and \(K\): The entire \(Q\) and \(K\) matrices are loaded from HBM to SRAM.

- Compute \(S\): The intermediate attention score matrix S is computed as \(S = QK^T\). The \(S\) matrix is then written to HBM.

- Load \(S\): The attention score matrix \(S\) is loaded back from HBM to SRAM.

- Compute \(P\): The softmax function is applied to \(S\) to compute the attention matrix \(P=softmax(S)\), which is then also written to HBM.

- Load \(P\) and \(V\): The attention matrix \(P\) and the value matrix \(V\) are loaded from HBM to SRAM. The output matrix \(O\) is calculated by the matrix multiplication of \(P\) and \(V\) (\(O = PV\)).

- Output: The output \(O\) is written from SRAM to HBM.

The main bottleneck in the vanilla transformer’s attention mechanism is the quadratic growth of the intermediate attention score matrix \(S\) and the attention matrix \(P\). If the input sequence has length \(N\), then the size of the matrices \(Q\), \(K\), and \(V\) are \(N \times d\), where \(d\) is the embedding dimension. However, the size of the intermediate matrices \(S\) and \(P\) are \(N \times N\). The sequence length \(N\) is typically much larger than the embedding dimension \(d\), and thus \(S\) and \(P\) are significantly larger than \(Q\) and \(K\). We are NOT able to do all computations in SRAM due to the limited capacity of SRAM. Therefore, the vanilla transformer requires data to move between HBM and SRAM several times. We call the vanilla transformer IO-unware as it does not account for the cost of HBM reads and writes.

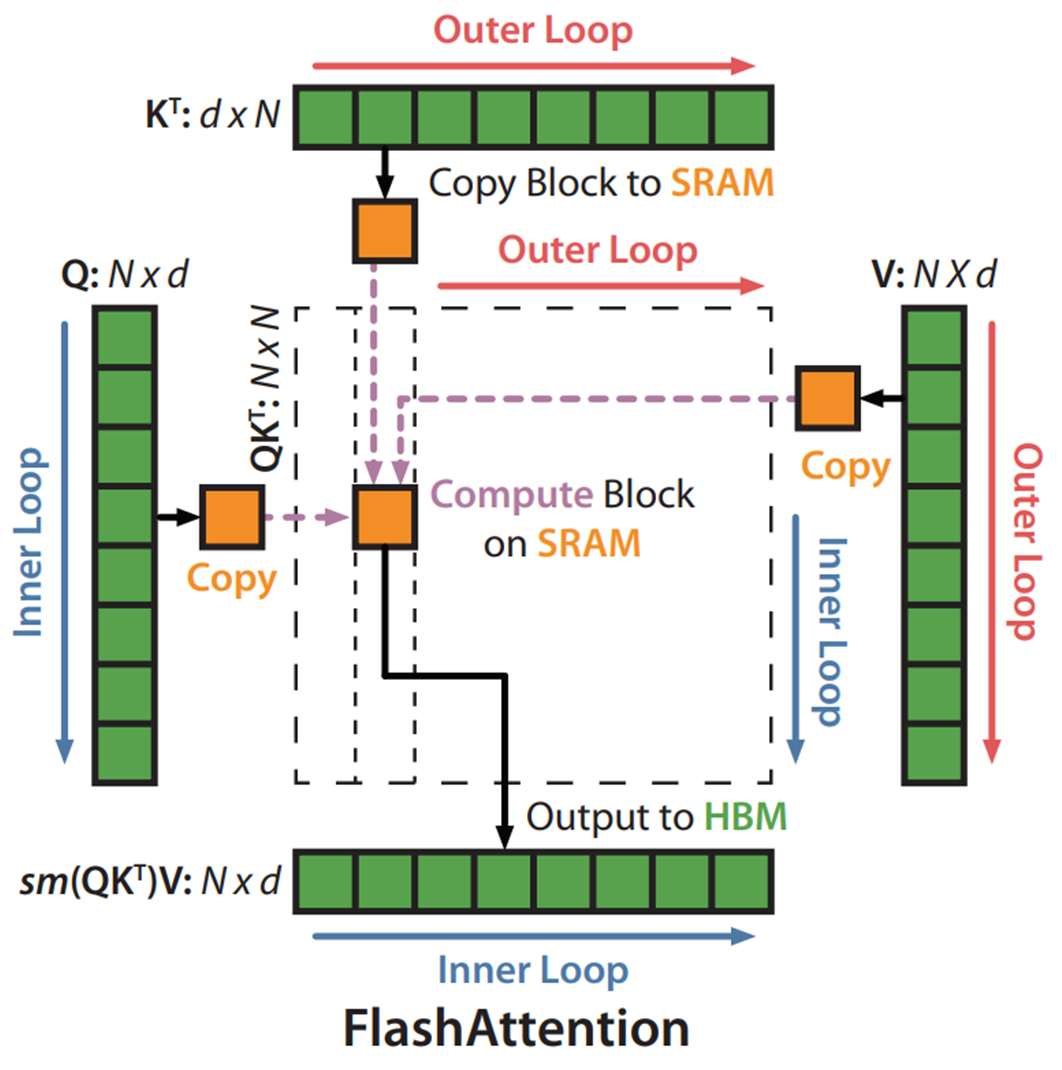

FlashAttention-1

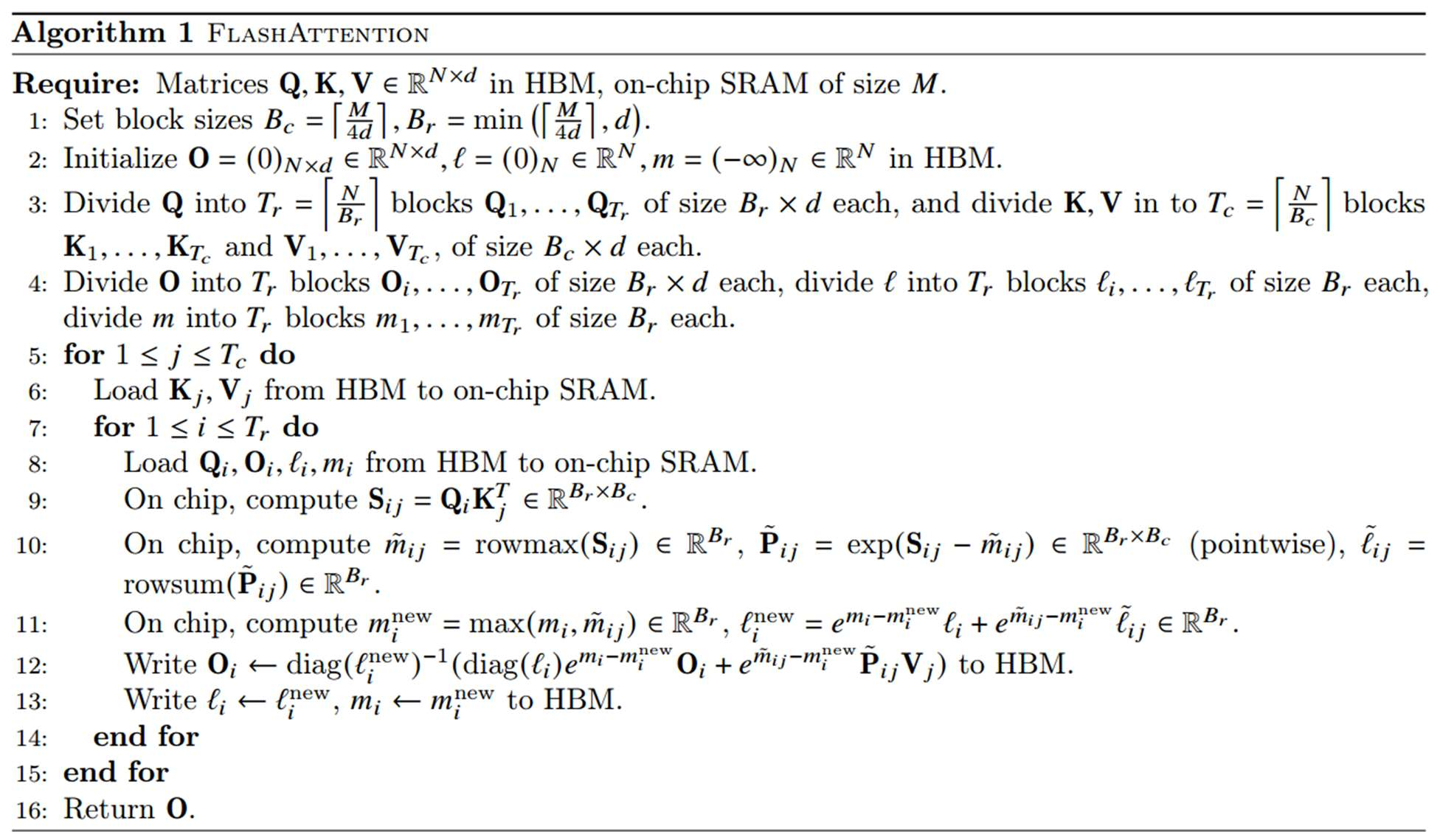

FlashAttention improves vanilla attention’s memory access by reducing the number of reads and writes to the relatively slow high-bandwidth memory (HBM) by using a tiling approach and recomputation.

Tiling: FlashAttention divides the input matrices (Q, K, and V) into smaller blocks, or tiles, rather than processing them all at once. Tiling enables us to implement our algorithm in one CUDA kernel, loading input from HBM, performing all the computation steps (matrix multiply, softmax, optionally masking and dropout, matrix multiply), then write the result back to HBM. This avoids repeatedly reading and writing of inputs and outputs from and to HBM.

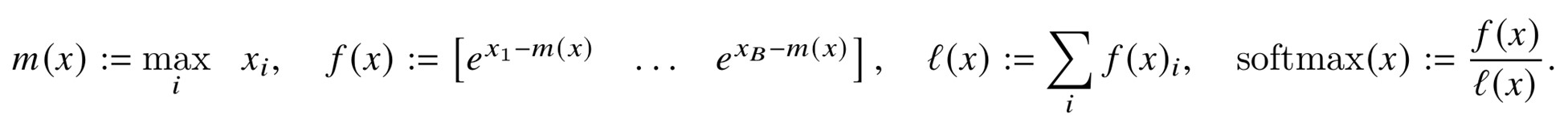

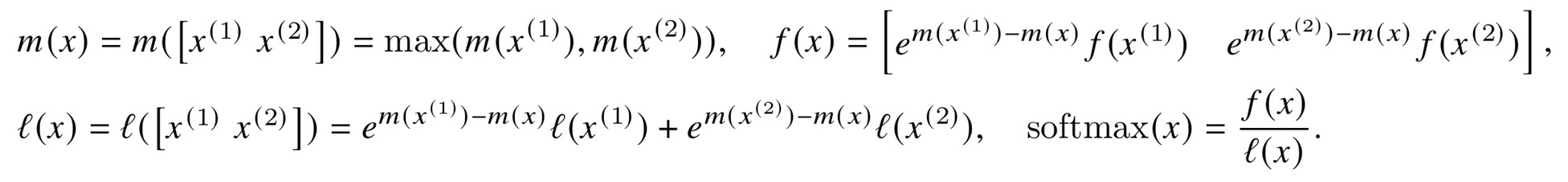

Online Softmax for Tiling: Due to tiling, we do not have the entire input vector x in SRAM for softmax computation. We need to compute softmax in blocks. The vanilla attention computes the softmax in this way.

FlashAttention computes softmax in blocks. Take two blocks as an example.

Therefore if we keep track of some extra statistics (m(x), l(x)), we can compute softmax one block at a time.

Recomputation: In the backward pass, FlashAttention avoids storing the large intermediate matrices S and P by recomputing them on-chip using softmax normalization statistics from the forward pass. While recomputation results in more FLOPs, it is still faster than reading from HBM because HBM access is slow. By recomputing the values of the attention matrices S and P once blocks of inputs Q, K, V are already loaded to SRAM, FlashAttention avoids having to store large intermediate values in HBM.

FlashAttention-2

FlashAttention-2 builds upon the original FlashAttention algorithm, introducing several key improvements to enhance performance, particularly in terms of speed and GPU resource utilization. While both algorithms compute exact attention without approximation, FlashAttention-2 focuses on optimizing work partitioning on the GPU, reducing non-matmul FLOPs, and increasing parallelism, leading to higher throughput.

- Reduced Non-matmul FLOPs: FlashAttention-2 is designed to reduce the number of non-matrix multiplication (matmul) floating-point operations (FLOPs) without changing the output. GPUs have specialized units for matrix multiplication, making matmul operations faster than non-matmul operations. Even though non-matmul FLOPs might be a small fraction of the total, reducing them allows the GPU to spend more time on the more efficient matmul operations.

- Increased Parallelism: FlashAttention-2 parallelizes the attention computation along the sequence length dimension, in addition to the batch and number of heads dimensions (as in FlashAttention-1). This additional parallelization increases GPU occupancy, especially when dealing with long sequences where batch sizes are often smaller.

- Improved Work Partitioning: FlashAttention-2 addresses the suboptimal work partitioning between different warps on the GPU that was present in the original FlashAttention. The wrap refers to a group of 32 threads that execute together on a GPU. FlashAttention-2 is then more efficient at utilizing the GPU’s resources, whereas the original FlashAttention could suffer from low occupancy or unnecessary shared memory reads/writes.

FlashAttention-3

FlashAttention-3 exploits the new hardware capabilities of Hopper GPUs. It introduces Producer-Consumer asynchrony, Hiding softmax under asynchronous block-wise GEMMs, and Hardware-accelerated low-precision GEMM.

Producer-consumer asynchrony involves splitting the warps into producer and consumer roles. Producer warps handle data movement using the Tensor Memory Accelerator (TMA) while consumer warps perform computations using the Warp Matrix Multiply Accumulate (WGMMA) instructions of the Tensor Cores. This division of labor enables the overlapping of data movement and computation, effectively hiding memory and instruction latencies and leading to improved GPU utilization. In contrast, FlashAttention and FlashAttention-2 do not explicitly separate data movement and computation tasks into producer and consumer roles.

Hiding softmax under asynchronous block-wise GEMMs. FlashAttention-3 introduces a novel method of overlapping GEMM (General Matrix Multiplication) and softmax operations. While softmax executes on one block of the scores matrix, Warp Matrix Multiply Accumulate (WGMMA) executes in an asynchronous proxy to compute the next block. This overlapping of operations ensures that the GPU’s resources are utilized more efficiently, as non-GEMM operations such as softmax are performed concurrently with the asynchronous matrix multiplications.

Hardware-accelerated low-precision GEMM. By leveraging hardware-accelerated low-precision GEMM, specifically targeting the FP8 Tensor Cores, FlashAttention-3 achieves nearly double the TFLOPs/s compared to higher precision. FlashAttention-3 employs block quantization and incoherent processing to mitigate the accuracy loss associated with low-precision. Block quantization involves dividing the input tensors into blocks and quantizing each block separately. Incoherent processing uses random orthogonal matrices to reduce quantization error.

References

[1] Dao, T., Fu, D., Ermon, S., Rudra, A., & Ré, C. (2022). Flashattention: Fast and memory-efficient exact attention with io-awareness. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 35, 16344-16359.

[2] Dao, T. (2023). Flashattention-2: Faster attention with better parallelism and work partitioning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2307.08691.

[3] Shah, J., Bikshandi, G., Zhang, Y., Thakkar, V., Ramani, P., & Dao, T. (2024). Flashattention-3: Fast and accurate attention with asynchrony and low-precision. arXiv preprint arXiv:2407.08608.